Treaties negotiated between the United States government and American Indians in 1851, 1863 and 1868 created some boundaries: physical, setting aside separate lands for separate tribes, and fiscal, promising the tribes compensation in the form of goods and/or monies. The treaties also included provisions intended to promote peace both among the tribes and between the tribes and whites.

Reformers embraced that idea and further, supported “civilizing” Indians in an effort to help them become self-sufficient and better able to live under the English common law system. One policy that resulted was the Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887, which its opponents saw as a method clearly intended to reduce tribal lands.

Treaties and tribal and government background

In 1871, the U.S. government stopped making treaties—a practice that had been in place for a century. Tribal power had been steadily slipping since the end of the War of 1812. By 1870 it was clear to all sides that treaties were no longer agreements between sides of anything like equal power.

Congress’s immediate problem with treaties, however, was political and internal. The problem stemmed from the constitutional provision that only Senate approval was needed for a treaty to become law. The House of Representatives had no say—but the House had to find the funds to pay for the food, goods and services the treaties promised.

In an act signed March 3, 1871, to fund the Indian Bureau that year, the House inserted an amendment barring the United States from ever again negotiating a treaty with an Indian tribe. Existing treaties—and their obligations—would continue with the same force of law. New agreements with tribes would be called just that—agreements.

Tribal approval, usually from this point on in the form of a majority vote of tribal members—would still be necessary before an agreement could go into effect. Even that system, however, was a blow to traditional, consensus-based forms of tribal government. [1]

Grant’s peace policy

Soon after taking office in March 1869, newly elected President Ulysses S. Grant, former general of all the Union armies in the Civil War, was approached by a variety of Quaker, Episcopalian and other Protestant reformers. Recent strife on the plains showed clearly that making war on native people produced no better results than diplomacy had, they argued. They pressed Grant to back policies outlined in two recent Congressional reports: Concentrate populations of Indian people on reservations, “civilize” them there with schools, Christianity and agriculture and clean corruption out of the Indian Bureau. And finally, replace the treaty system with something more flexible that, supposedly, would better meet the needs of the Indian people.

Early on, Grant placed 18 Quakers and 68 Army officers in Indian agent positions throughout the West. But after a squadron of cavalry attacked a Piegan Blackfeet village on the Marias River in northern Montana Territory in January 1870—killing 173 people, mostly women and children and many of them sick with smallpox—Congress, in shock and backlash, outlawed the appointment of any Army officers to civil posts. Grant then divided all the agency positions among different Protestant denominations. By 1872, 73 different Indian agencies had religious agents. It was a constitutionally dubious alliance between state and church that would have profound effects on Indian people in the coming decades. [2]

By the summer of 1877, war had ended on the northern plains between the Army on one side and, the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne and Northern Arapaho on the other. The Eastern Shoshone signed a treaty with the government in 1868 guaranteeing them a reservation on Wind River in what soon became Wyoming Territory. After repeated government failures to come up with any other solutions, the Northern Arapaho joined the Shoshone on Wind River in 1878. Across the West, the reservation era had begun.

Reform politics and the General Allotment Act

In 1883, a group of Protestant reformers began meeting every fall at a resort on Lake Mohonk in the Catskill Mountains north of New York City. These included many clergy, as well as academics, merchants, bankers and a few tycoons. They thought much like the reformers who had pressed President Grant for a peace policy a decade and a half before. They valued progress, hard work, Christian living and private property, and they considered themselves deeply committed to the future of Indian people.

These reformers, historian Robert Utley notes, “saw nothing worth saving from the past, and they had not the slightest doubt of the rightness and righteousness of their vision of tribal destiny.”

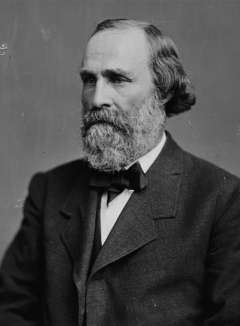

Among the Lake Mohonk reformers was U.S. Sen. Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts. He enthusiastically went along with the reformers’ agenda, which began with Grant’s peace policy but had roots reaching back to colonial times. The policy’s main goals were “civilizing” Indian people through several means: self-sufficiency through agriculture; education; Christianity; protection of rights and punishment for transgressions as understood in English common law; and—key to all the rest—individual ownership of separate, individual plots of land.

In order to make these changes possible, Dawes and the other reformers agreed, it would be necessary to do away entirely with tribes and tribal identity among Indian people. The family would now be the basic unit. It would also be necessary, eventually, to do away with Indian reservations altogether. This would allow tribes to be more easily assimilated and absorbed into the general United States population and culture. By making these changes, the reformers thought, the Indian Bureau and all government bureaucracies dealing with Indian policy would be quickly purged of their incompetence and corruption and would wither away.

Finally, once Indian land could be divided and allotted to individual Indian owners, the so-called surplus land—of which there would be a great deal—could be thrown open for white homesteaders. With the exception of their small, individual plots, the tribes would lose all the rest of their land. “This argument,” Utley writes, “appealed to almost everyone.”

Provisions of the Dawes General Allotment Act

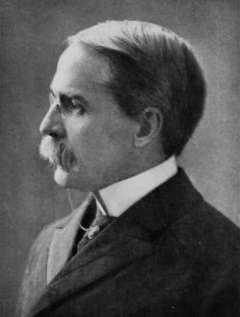

On Feb. 8, 1887, President Grover Cleveland signed the Dawes General Allotment Act into law. These are its main provisions:

The idea of allotting lands to individual Indians was not new, but the end result—free and clear title as well—was new. To supporters in Congress and elsewhere, this looked like a positive change. True ownership as understood under Anglo-Saxon legal traditions would theoretically protect individuals from abuses like the ones that had afflicted the Cherokee 50 years earlier, for example, when they were separated from their land and shipped west on the Trail of Tears. It would also, reformers agreed, bolster Protestant ideals of hard work and people’s enjoyment of the fruits of their own labors, in contrast to tribal customs of always sharing with neighbors, friends and kin.

At one of the Lake Mohonk conferences, Amherst College President Merrill E. Gates had argued that Indians need to be taught to be “intelligently selfish.” They should be “got out of the blanket and into trousers,” he said, “and trousers with a pocket in them, and with a pocket that aches to be filled with dollars! ” [italics in the original].

But Congress was by no means unanimous in its support for the new law. Members of the House Committee on Indian Affairs who disagreed with the proposed legislation issued a minority report. “The real aim of the bill is to get land out of Indian hands and into the hands of white settlers,” the dissenters wrote. “If this were done in the name of Greed, it would be bad enough, but to do it in the name of Humanity, and under the cloak of an ardent desire to promote the Indian’s welfare by making him like ourselves, whether he will or not, is infinitely worse.”

Congress on its own—not being required to seek tribal approval—continued making amendments to the Dawes Act. Laws passed in 1891 and 1895 provided that any allotments not used productively, in the judgment of government agents, could be leased to others. Any individual who did not occupy, use and improve the land could lose his allotment.

Later, Theodore Roosevelt would call allotment “a mighty pulverizing engine, to break up the tribal mass.” [3]

After the turn of the century, all these developments mattered a great deal on the Shoshone Reservation where the Northern Arapahos were living as well. But first, the government approached the tribes for still more land. Lands in tribal hands nationwide before the Dawes Act totaled about 138 million acres. By 1934, after nearly 50 years of allotment, only 48 million acres remained in tribal hands. [4]

The skepticism of the congressmen who saw the Dawes Act as primarily a way “to get land out of Indian hands” was, apparently, entirely justified.

The Dawes Act on Wind River

The Dawes Act, by dividing the landholding power of Indian people on Wind River into hundreds of small pieces, reduced their power even further at a time when starvation and disease were decimating the two tribes. And as the land was divided, so was the politics. In 1895, needing cash, the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho agreed by majority vote to sell to the hot springs at what’s now Thermopolis, Wyo., to the U.S. government for $60,000. [5] This new system—the ballot—was a huge shift from the old decision-making systems of council and consensus that had prevailed in the tribes for centuries.

In 1905, both tribes, again by a majority of individual ballots cast, approved a far more complicated agreement ceding hundreds of thousands of acres north and east of the Big Wind River. Many allottees south of the river soon found themselves in still more difficult circumstances, waiting for payments that seldom came while facing new debts and obligations that often forced them to sell their land.

The U.S. government’s decades-long drive to reduce the power of Indian people would reach its apex in the 1950s and 1960s, when Congress did away with many tribes entirely. The Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho, fortunately, were able to resist that movement, and, eventually, to hold on to their culture, some of their water rights, and much of their land.

Editors’ Note: This and other 2018 and 2019 articles and digital toolkits on the history of tribal people in Wyoming in are possible with support from the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, the Wyoming Council for the Humanities and several Wyoming school districts, including districts headquartered in Fort Washakie, Arapahoe, Shoshoni, Lander, Powell, Laramie, Douglas and Afton, Wyoming. WyoHistory.org extends its thanks to all.

Texts and other background sources

[1] Robert M. Utley, The Indian Frontier of the American West, 1846-1890 . (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003), 132; Janet Flynn, Tribal Government: Wind River Reservation . (Lander, Wyo.: Mortimore Publishing, 2008; reprint; first edition published 1991), 29-31.

[2] Henry E. Stamm, IV, People of the Wind River: The Eastern Shoshones, 1825-1900 . (Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999), 53,58; Utley, 130-132.

[3] The U.S. government granted citizenship to Indians in the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, also known as the Snyder Act. See more in Johanna Wickman, “Touring the Reservations: The 1913 American Indian Citizenship Expedition,” WyoHistory.org, accessed Oct. 13, 2018, at /encyclopedia/touring-reservations-1913-american-indian-citizenship-expedition . Roosevelt quoted in Charles Wilkinson, Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations , (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2005), p. 43.

[4] Utley, 196-207, “intelligently selfish,” “got out of the blanket …” and “This argument appealed …”, 205. Loretta Fowler, 87; Flynn, 21-23, “If this were done in the name of Greed …”; figures on acreage of tribal lands before and after allotment, 23.